‘Change is possible’: Parents involved in Larimer County justice system learning how to nurture their families

The Matthews House creating access to behavioral health services, resources through Parent Café

Sitting at a small table in the women’s residential facility, next door to the Larimer County Correction Center, she shares her hopes and reflections with four other women on a chilly evening in mid-February. Sepulveda wants to be the mom she was before years of substance use, and relapses, and recovery separated them.

“You stay in contact with him, right?” fellow mother Jaime Brown, says, bringing Sepulveda’s attention to the hand-written card she just sealed in a blue envelope and addressed to her son. “You have a chance to be a better parent than the day before.”

Sepulveda agrees and thanks Brown. The two women are part of what they call “Comp Court,” otherwise known as the 8th Judicial District Competency Docket. In 2021, it was recognized as the first in the state to streamline the court process for those with persistent mental health concerns in Larimer County.

They are also regular attendees and ardent supporters of the Parent Café program, put on by The Matthews House to empower parents and caregivers through education, skills development, community building, and resources designed to nurture themselves and their families.

The café model has been around for decades nationally and is open locally to all parents and caregivers. Thanks to a Larimer County Behavioral Health Services Impact Fund grant, the Matthews House has been able to offer more Parent Café sessions for men and women who are incarcerated at the Larimer County jail or in the Work Release program.

“For me, it removes the stigma of mental health,” said Sepulveda, “It gets people the help they need.”

Her voice breaking with emotion, Parent Café facilitator Diane Clark said she’s “happy to live in a community that supports others.”

“Behavioral health is so important, so people don’t get out of jail and come back,” she said, when asked what it might look like if the Parent Café or Larimer County behavioral health sales-use tax didn’t exist. “It makes the community stronger, and it saves the community time and money.”

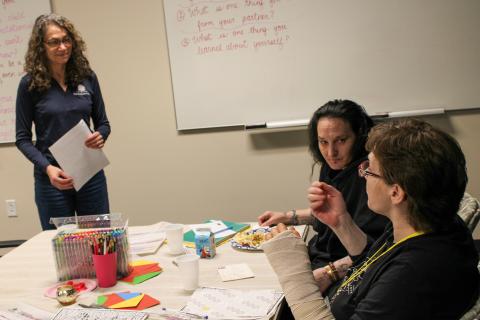

Clark focuses her lessons on five protective factors, including parental resilience, social connections, knowledge of parenting and child development, concrete support, and the social and emotional competence of children. In a recent Café session, the group learned about how a person’s attachment style affects their parenting style. Discussions centered around setting appropriately high expectations and balancing structure with nurturing care.

“When my parents were parents, they didn’t have all this information,” said Sepulveda. Clark agreed, noting that there is no judgement around that truth: “They were doing the best they could with what they had.”

Brown, who says she has taken every class she can, hopes to get out on parole in August. Working the program, she says, is her working on herself, so she is a better influence for her son.

Jennifer Griffiths is a justice-involved case worker and Parent Café supervisor with The Matthews House. For many of the men and women with whom she works, the Parent Café sessions are “absolutely” their first introduction to behavioral health care.

“Sometimes they don’t know what to ask. They don’t know what’s available. Sometimes, they might not think that people are invested in wanting to help them,” said Griffiths, who helps people get connected with resources in her role as case worker.

“We all want to find that connection and have those chances. We always have options,” she said. “We always have choices.”

For those in jail or Work Release, the Parent Café is a 12-week program. During that time, they learn about themselves and from one another. Griffiths has “heart-to-heart talks” with people; strives to be a source of hope; and helps them identify steps to living a different life. She helps them to secure housing and work, which can be difficult for people with a criminal record, as well as reunify them with their children.

People can voluntarily participate in case management and the Parent Café program. Griffiths said they meet each person where they are at, build upon their skills, and work toward their goals.

“Working with justice-involved families is deeply personal for me, as I bring my own lived experience and the challenges of navigating the justice system with my son,” said Griffiths, who understands the frustration, fear, and hopelessness that individuals and families may feel.

“My goal is to empower caregivers and families by providing guidance, resources, and support, helping them heal, rebuild, and create lasting change,” she said. “Change is possible, no matter how difficult the road may seem.

I needed someone to remind me that I could build a better future, and I know firsthand how important it is to have someone believe in you when you’re at your lowest.”

The Matthews House Parent Café program

- Sessions are available in English and Spanish.

- They are open to all parents and caregivers.

- Registration is required for all sessions.

- Learn more

Madeline Novey

Communication Specialist

Behavioral Health Services

970-619-4255

noveyme@co.larimer.co.us