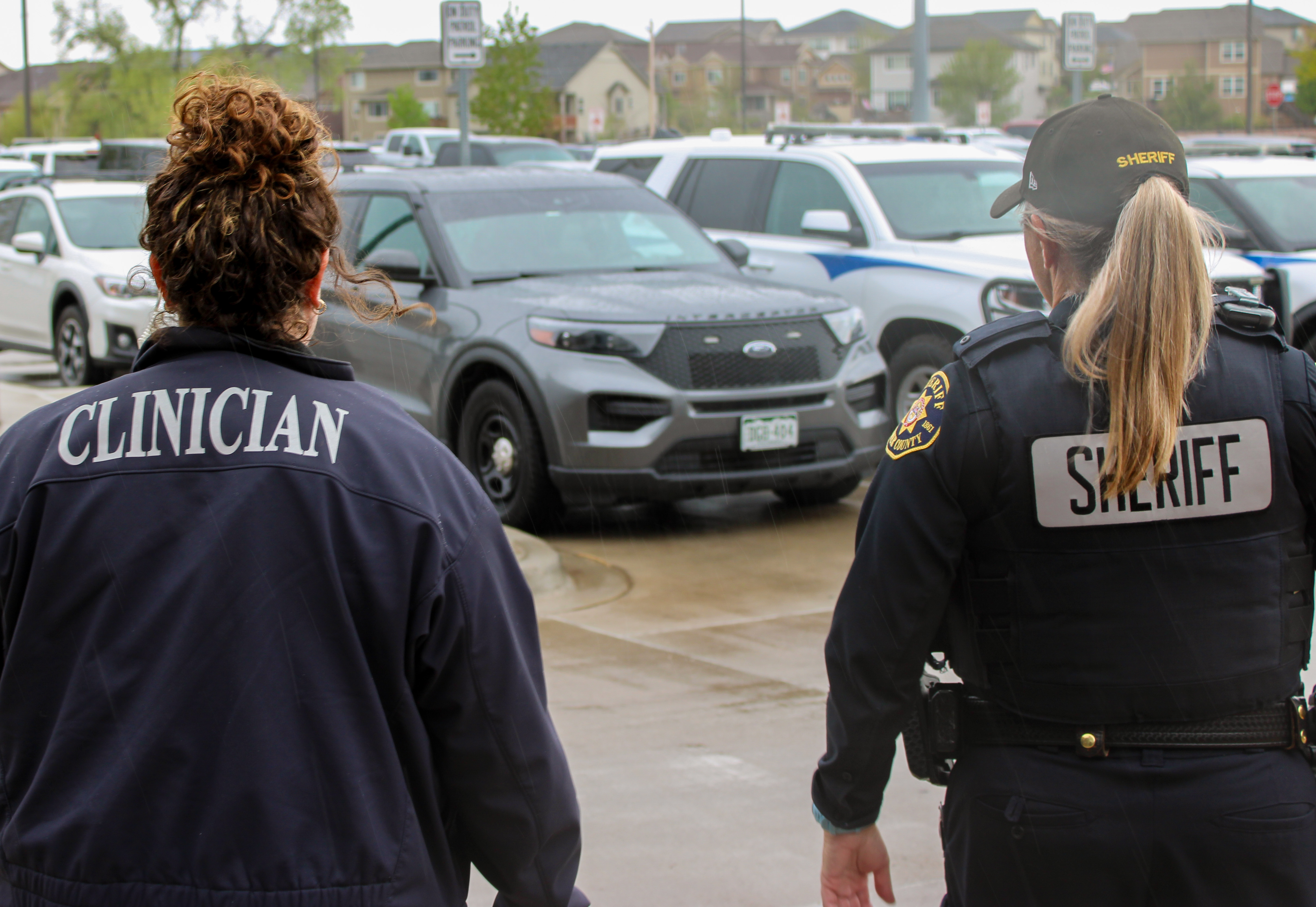

Larimer County co-responders provide compassionate care amid behavioral health crises

The police report was eyebrow-raising: A meth lab hidden in a retirement community.

But the more the elderly adult shared, the more confusing things became. There were disjointed sounds, smells, and memories.

The police officer and co-responder clinician, Sue Jones, who met the individual in the Loveland Police Department lobby, were kind and patient as they asked questions. They commended the person for having the courage to say something.

They also took down a friend’s phone number to follow up – because the individual couldn’t remember their own number, and their phone was dead.

When Officer Ben Hasani finished taking the report, Jones, a licensed clinical social worker, asked the individual how they were sleeping and managing stress from the situation. Jones learned the individual was a long-time healthcare worker before retirement and wanted to determine what support they may need.

“You have served so many people. Now it’s my turn to serve you,” said Jones.

Visibly appreciative, the individual said, “You’re going to make me cry.”

As they built rapport, Jones tactfully said she was concerned about the individual’s memory and that she and the officer had been assessing for a possible cognitive impairment.

The two made a plan to connect with the person’s doctor. Then Jones called the individual’s friend to pick them up.

“You are amazing,” the person said. “Thank you for what you do.”

Jones is not only a social worker but a co-responder since 2019. This group of professionals has a long history but has been growing more rapidly in recent years, as communities try to tackle the nation’s increasing demand for behavioral health support.

The first co-response teams paired police officers and mental health professionals to respond to crisis calls in the 1970s and 80s, according to the International Co-Responder Alliance. Communities have varying approaches, but the common goal is to provide mental health support and resources to individuals in crisis, de-escalate situations, and potentially avoid unnecessary arrests, incarcerations, or hospitalizations.

Teams are popping up across the U.S., but Colorado still had the most, as of early 2025, said Jessica Murphy, chair of the International Co-Responder Alliance and deputy division director in Johnson County Kansas. It is home to one of the nation’s early co-responder programs.

The Larimer Interagency Network of Co-Responders (LINC) is made up of multiple organizations, including but not limited to Larimer County, Larimer County Sheriff’s Office, Loveland Police Department, Fort Collins Police Services, SummitStone Health Partners, UCHealth, and Estes Park Police Department. A Program Coordination group for LINC was established in 2018 to expand co-response efforts throughout Larimer County, and leaders from across the community continue this collaborative work today.

Larimer County is fortunate to have multiple teams:

- UCHealth clinicians are paired with Fort Collins Police Services officers to respond to calls in the City of Fort Collins.

- SummitStone Health Partners clinicians are paired with Larimer County Sheriff’s Office deputies to respond to calls across Larimer County.

- At Loveland Police Department, SummitStone co-responders go alone to calls within the City of Loveland, and can request support from an officer if needed.

- There is one SummitStone co-responder for Johnstown, and one for Estes Park.

- Other local agencies have contracts with LCSO for co-responder support, as needed.

Larimer County Behavioral Health Services is proud to partner in this work, as a funding administrator, to support co-response across our community.

No day is like another for co-responders. They might assess a person at risk of suicide, work with Child Protection Services to connect a family to services, help a person in distress find housing, or take an individual actively experiencing psychosis to a crisis center like Larimer County’s taxpayer-funded Acute Care at Longview campus.

“No matter what the call is, we’re always trying to do right by the person in crisis. We’re always functioning with their best interests in mind,” said Megan Hencinski, a licensed clinical psychologist who manages SummitStone Health Partner’s co-responder programs.

Before coming to Colorado, Hencinski worked in state psychiatric facilities and jails, and started the City of Alexandria Co-Responder Program in Virginia. The community was seeing the same people stuck in the system, Hencinski said, and it was “almost too late” by the time they were at the hospital.

The co-responder model aims to intervene earlier, provide more individualized and timely care, and free up emergency rooms and jails from patients that are better suited for other facilities.

“It’s beyond just the call for service,” she said. “It’s being able to provide education and resources. Being able to connect people to the behavioral health system, which is challenging for any of us to figure out on our best days.”

Although teams at each Larimer County law enforcement agency track data differently, all say they’ve seen an increase in the volume and intensity of calls in recent years.

It could be that more people are experiencing more significant mental illness and substance-use issues. More people could be open to seeking care, as society chips away at the persistent stigma around mental health. Or it might be that more people know about the co-responder teams and call more often.

Regardless of the reason, the teams are committed to building trusting relationships, giving individuals the right care at the right time, and taking the weight of mental health calls off of other emergency responders’ shoulders – thus freeing them up to respond to fires, thefts, car crashes, and more.

“It’s rewarding, but I feel a huge responsibility to not fail them,” said Larimer County Sheriff’s Office Deputy Cheryl Jacobs, of the clients she and her clinician partner, licensed clinical social worker Nickole Kalinay, serve. She and other co-responders work hard to build trust in the community and respond to calls in ways that are different from decades past.

But through things like the Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT, training that Jacobs does, participants learn about different diagnoses and practice responding appropriately through role-play scenarios.

“That the policy and the outlook has changed is good,” said Jacobs, commending LCSO for its support of CIT training and other agency shifts related to behavioral health.

Down south at Loveland Police Department, Jones starts the small, white co-responder van and heads to a local middle school, where a principal is concerned about a student. Seated across from the student on a bean bag in the calm room, Jones asks questions to determine if they are a threat to themself or others.

Jones’ will make a plan for the student to receive support over the summer, when they no longer have access to the social worker at school. This is a big part of the work: coordinating with other professionals and organizations and getting people connected to services, be it talk or music therapy, groups that foster a sense of belonging, or medication.

At one point, a staff member pops into the calm room and tells her that a different student, who was struggling significantly before, is now coming to school and doing well. Jones smiles and thanks her.

“We don’t always hear the end of the story,” she says, later adding, “It’s those little glimmers, those little shimmers, that keep us going.”

In their first-floor office at the police department, Jones and her fellow co-responder, Jessica Brickey, a licensed professional counselor, debrief calls and brainstorm ways to help each individual. Colleagues from different departments, including officers, stop by to check on cases or thank them for helping on a recent call.

They like being able to advocate for people who don’t necessarily have a voice – those people who are most vulnerable or having the worst days of their lives.

Jones said she wishes that more people knew about the resources available in Larimer County and that they weren’t afraid to call for help. There are barriers to seeking help, she said, whether it’s mental health stigma, not wanting someone to be mad at them for calling, or myths that confronting someone about suicide will cause the person to do it. (It won’t.)

Most people aren’t aware of what’s in our community if or until someone they know needs support. That’s normal, and more proactive education is needed. Just like we teach children to call 911 when someone breaks their leg, we need to teach people who they call when it’s a mental health emergency.

If you only remember these, Brickey and Jones agreed, staff at each will help you get to where you need to go. There is “no wrong door.”

- Acute Care facility at Longview campus, 2260 W. Trilby Road, in Fort Collins. Call 970-494-4200 ext. 4.

- The behavioral health urgent care is open 24/7/365 to people of all ages.

- After being assessed for a self-described behavioral health crisis, individuals may be admitted to the facility for withdrawal management or short-term, overnight care.

- SummitStone Mobile Crisis Response. Call 970-494-4200 ext. 4, day or night.

- Responds to calls in all of Larimer County.

- Staff will assess the individual, help with de-escalation and determine if they need a higher level of care or connection to other services.

- Co-responder teams

- Loveland Police Department: 970-962-2894.

- Larimer County Sheriff's Office: 970-416-1985.

- Mental health resources are also on the Larimer County Sheriff's Office website at www.larimer.gov/sheriff/mental-health-CRU.

- Call 911 now if you or someone you know is currently having thoughts of suicide or a threat to others.

Jones drew a line between behavioral health and advertising.

“Sometimes, people need 100 contacts to move forward and get help for their behavioral health. Maybe we’re at 87 today, and we’re (the co-responder) making progress.”

Whenever and however they can help, co-responder teams are having a positive impact within Larimer County’s behavioral health system. And those involved in the work today predict that will continue as the programs grow.

Get crisis help when you need it. There is “no wrong door.”

- Acute Care facility at Longview campus, 2260 W. Trilby Road, in Fort Collins. Call 970-494-4200 ext. 4.

- The behavioral health urgent care is open 24/7/365 to people of all ages.

- After being assessed for a self-described behavioral health crisis, individuals may be admitted to the facility for withdrawal management or short-term, overnight care.

- SummitStone Mobile Crisis Response. Call 970-494-4200 ext. 4, day or night.

- Responds to calls in all of Larimer County.

- Staff will assess the individual, help with de-escalation and determine if they need a higher level of care or connection to other services.

- Co-responder teams

- Loveland Police Department: 970-962-2894.

- Larimer County Sheriff's Office: 970-416-1985.

- Mental health resources are also on the Larimer County Sheriff's Office website at www.larimer.gov/sheriff/mental-health-CRU.

- Call 911 now if you or someone you know is currently having thoughts of suicide or a threat to others.

Madeline Novey

Communication Coordinator

Behavioral Health Services

970-619-4255

noveyme@co.larimer.co.us